You Can't Even Dream a Whole Dream

Alexandra Tanner’s laugh-out-loud debut, “Worry,” casts the Internet as a tool for control.

Content Warning: This review includes a brief mention of suicide.

Two years ago, I subscribed to Kickstarter’s newsletter, “The Creative Independent,” in hopes that it would make me more creative and more independent. I don’t know if I’ve made much progress in either arena, but I have discovered a lot of worthwhile art. I’m pausing my “art as friends” series to write about one such piece.

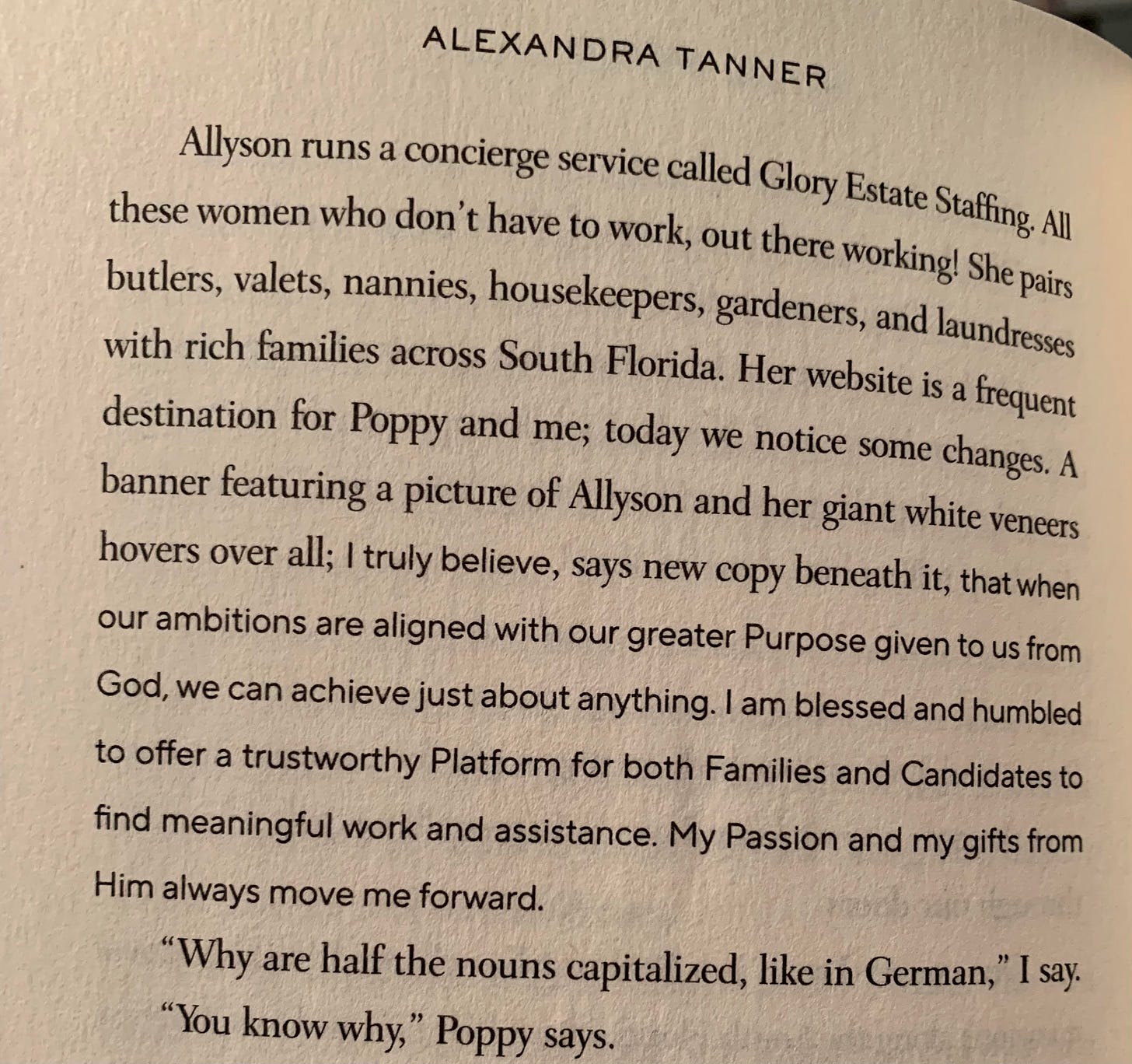

Alexandra Tanner’s novel “Worry” follows Jules Gold, an MFA graduate living in Crown Heights and working for a Sparknotes-esque website. It’s 2019; Jules is 28 but says she’s 30. After the end of a relationship and the collapse of her social life, she becomes fascinated by a community of Instagram “mommies” she follows from a burner account—Mormon women, anti-vaxxers, preppers. Even Jules’ own mother begins hawking oils as she turns to Messianic Judaism. She’s never happy with Jules or her younger sister Poppy, and she’s especially critical when Poppy comes to stay with Jules while looking for a job and place of her own in New York.

In Jules’ eyes, Poppy is a mess. She arrives “dressed ugly and covered in hives.” The two fall into a routine both cozy and claustrophobic—television marathons, getting high, endless scrolling, city walks. Jules is the only one who knows that Poppy attempted suicide a year ago, while living with their parents. She holds her sister gingerly but seethes with resentment, picking petty fights and blaming Poppy for her ennui.

Tanner is dialed into the 2019 setting, a snapshot of a particular Internet age when issues eventually laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic were just starting to fester. She captures the cyclical nature of codependency—the subtle manipulations, realizations, conflict, and forgiveness—in the sisters’ lived-in relationship. In one scene, Jules and Poppy get dinner with Poppy’s coolly insensitive college friends. When Jules criticizes them, Poppy acknowledges her friends aren’t perfect but rushes to defend them—I’ve been both sisters here, and I empathize deeply with each of them. And a Thanksgiving dinner scene back in Florida made me absolutely guffaw.

The more we get to know Poppy, the more we realize she might not be such a mess. She isn’t afraid to voice her beliefs. She looks outside herself, adopting a three-legged dog named Amy Klobuchar. She adapts to New York quickly, knocking down the defenses it took Jules years to build, and even literally takes her sister’s old job. Jules is quick to cast Poppy as a burden, but she’s just as quick to falter without her. When Poppy pursues her own interests or fails to text her sister back, Jules teems with jealousy and fear.

And, above all, Poppy dares to dream. One night, inebriated, she tells Jules about a detailed fantasy for her life. It begins:

“I’m at the Met in the middle of a weekday. I drop a glove in that big room full of the marble sculptures, and a kind tall dark handsome stranger picks it up and hands it back to me, and he compliments the glove, it’s velvet—it’s a velvet glove—and I make a joke, and he asks if I’m free for dinner…”

At the end of her fantasy, Poppy pukes, and Jules stews. “I’m jealous that Poppy can articulate such a clear, raw vision of want, that she can fantasize so deeply. Every time I think of something I want I manage to talk myself out of it.”

I’m reminded of a scene in the movie “The Holdovers,” when grizzled boarding school teacher Paul Hunham (Paul Giamatti), bereaved kitchen manager Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph), and left-behind student Angus (Dominic Sessa) are watching television together one night. Paul shares his hope to finish a monograph about Carthage one day. “Why not a whole book?” Angus asks, and Paul bristles.

“I’m not sure I have an entire book in me.”

Mary sighs. “You can’t even dream a whole dream, can you?”

But to let yourself dream would be to relinquish control, and control is all Jules has in a world she feels is happening to her, a world in which she’s not sure she can make art at all. Who knows whether Poppy will retain her hope when she’s Jules’ age or become as jaded as her sister, but at least now she hopes for better, while Jules lets irony rule her life. Although she tells herself she stands apart from the “mommies” she follows, observing them with a critical eye for an essay she’s yet to start, she’s increasingly pulled into their worlds, captivated by the certainty of their beliefs, and, dare I say, under their control. Jules starts fights in the comments section, monitors their daily moves, and, in a vulnerable moment, feels genuinely stirred by a video of a mommy praying over her followers. And, in the book’s somewhat unsatisfying final scene, when things feel spectacularly out of control, it’s the mommies to whom Jules turns.

In hard moments, sometimes we cope by turning up the volume outside our head. Tanner said it best in her interview with “The Creative Independent”:

“In times of uncertainty, whether it’s personal, professional, global, you want that chorus of people that you’re looking at, to live inside someone else’s thoughts for a second.”

I’m glad I could live inside Jules’.