Turning into Desire

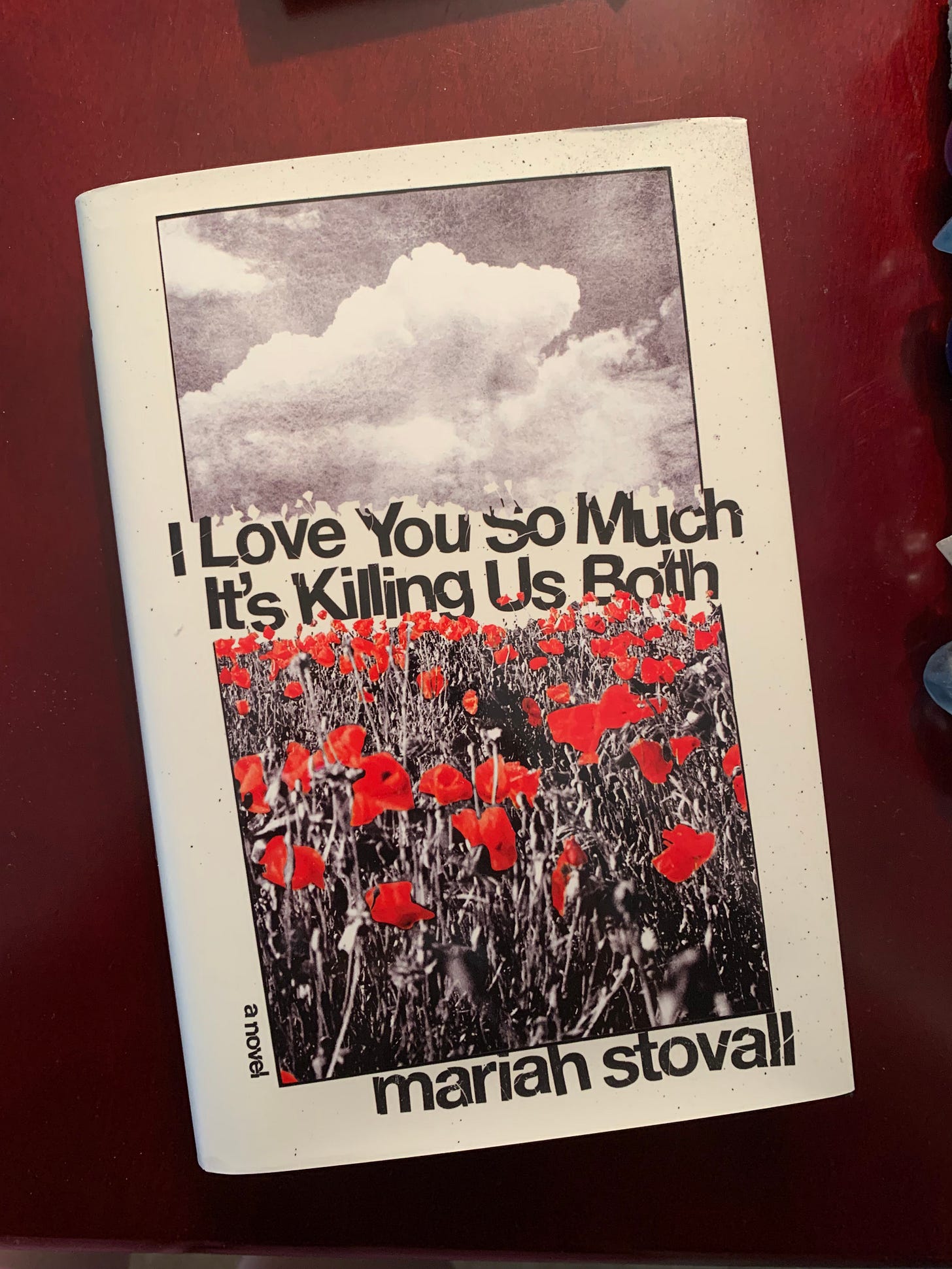

A review of "I Love You So Much It’s Killing Us Both" by Mariah Stovall.

I think a lot about Caroline Polachek’s album “Desire, I Want to Turn Into You.” When I first heard the title, I interpreted it to mean “leaning in” to desire, but I also considered how it could mean physically becoming your hunger. That’s what happens to Khaki Oliver, protagonist of “I Love You So Much It’s Killing Us Both.” Named for the Jawbreaker song, Mariah Stovall’s debut sets a story of all-consuming obsession against the backdrop of the 2010s indie punk scene.

When Khaki’s estranged best friend, Fiona, invites her to a party to celebrate her adopted daughter, Khaki is flooded with long-suppressed memories. In her late 20s, she leads a solitary life, working at a museum’s front desk, maintaining few friendships, and letting her records gather dust. But the invitation cracks her open, and, as Khaki decides whether to attend the party, she curates a mixtape chronicling her tumultuous bond with her old friend.

The fact that this novel is an “annotated mixtape” easily could be missed; the footnotes for each song could be mistaken for ordinary chapter numbers, and the track list is hidden at the end of the novel. Maybe Stovall wanted to avoid alienating those not familiar with a niche music scene, but foregrounding the music could have added more color and context to this claustrophobic story of a codependent friendship.

We get to know Khaki as a college freshman in 2011. She moved to California because of Joyce Manor, relishes the controlled chaos of a mosh pit, and, consciously or unconsciously, pushes away those closest to her. Khaki restricts and purges food, blocks and unblocks Fiona’s number, and treats a hapless boyfriend, Matty, like trash. Her best friend is her roommate, Cameron, an amiable stoner with a budding (ha) interest in punk. “Are the Arctic Monkeys punk?” he asks. (A few chapters later, he’s taking over the student arts center.) The center of their social life is the dining hall, where Cameron’s binges contrast starkly with Khaki’s restriction.

Stovall excels at capturing college during this era, introducing classmates who dance to Skrillex at foam parties one moment while joining the Occupy movement the next, who grapple with sex-positive feminism, and who reckon with privilege while lobbing microaggressions. In one standout scene, a concerned dean confronts Khaki about her eating disorder and calls her by another light-skinned Black student’s name. Flustered, Khaki wonders how he discovered something she doesn’t quite understand herself—her desire is a mystery even to her.

“I didn’t—understand why my nail polish chipped off in my throat in my favorite single-stall bathroom in the basement of a certain academic building every Monday afternoon—understand how to sate a desire that itself was the absence of wanting, or the epitome of it—understand why I wanted to want everything without needing anything, which was obviously impossible—understand how someone could have told him what they’d told him without my consent.”

Likewise, Stovall’s depictions of punk shows are impressionistic but strong, capturing the unspoken rules that can make a rowdy crowd feel like the safest, most unified place in the world.

“Shin to forehead, shoulder upon shoulder, watching out for each other, percussive concussions, knuckle to ear to busted lip, crying And that’s when I knew you were dead. This was safer than the sudden onslaught of strangers on a bus. We repeated without rinsing, seeped more with every song and set. Clapped. Howled. Demanded. Lose your voice and make it hurt.”

Yet the music fades away, and the depiction of Khaki’s disordered eating becomes graphic and grueling, bordering on trauma porn. It’s hard to watch her abuse her loved ones, and, while unlikable characters can be compelling, it’s hard to figure out Khaki. How much of her trauma is her own? How much is Fiona’s that she’s taken on?

It’s a relief, then, when Stovall flashes back even further, to high school, to chronicle the early days of Khaki and Fiona’s friendship. Khaki, reeling from her parents’ separation and a resulting move, and Fiona, fresh out of inpatient treatment for her eating disorder, become fast friends in a class of chattering, Harry Potter–loving girls Khaki calls “Alisons.” Understanding Khaki’s all-too-familiar trauma from past romantic relationships helps contextualize her cruelty toward her college boyfriend, and I hoped for the same insight into Fiona. After such an agonizing description of the pain their friendship wrought, I was eager to get to know this enigmatic character.

But Stovall doesn’t give us much to like about her. Fiona loves God and doesn’t love punk. Resentful of her friend’s new passion and ideals, she inserts herself into Khaki’s relationships with devastating results. The girls’ friendship is marked by jealousy, possessiveness, and fights about the burden of keeping Fiona afloat. Their few moments of joy and levity—spent teasing out word pairs and learning the scientific names of plants—feel manufactured and contrived. I don’t know if I buy their relationship! But when I think about the power of an intense, cerebral connection in a time of loneliness, and I reflect on my own all-consuming relationships, often with people who haven’t treated me well, I can just as easily imagine someone raising an eyebrow in the same way—“You’re letting them get to you?” And sometimes, challenging relationships don’t always culminate in grand epiphanies, or in character growth at all. When the novel returns to the present-day, Khaki’s still making shockingly bad decisions and fumbling through life—but maybe, this time, with a new perspective.

This novel could have benefited from a more astute editor; I found several typos. Tightening and restructuring could have made this sojourn with two grating characters more gratifying and further centered the music that keeps our protagonist afloat. But, even though I felt frustrated reading it, this book destroyed me a little, holding up a mirror to some of the fears and the feelings I hide. Maybe I’ll make a mixtape about it.