THRESHOLDS: Turnstile

Amid the weight of fame, the Maryland band clings to home.

THRESHOLDS is a series about artists at transitional stages in their careers.

I’m not going to pretend I’ve been a day 1 Turnstile fan or that I’m a hardcore scholar. If you want to hear from someone who is, read Eli Enis’ Stereogum piece on the Baltimore band’s new album, “Never Enough.” I’m just a woman from Maryland who wants to talk about what Turnstile means to me.

I found the band in 2021 with their breakthrough album, “Glow On.” Pitchfork gave it Best New Music. Photos of their benefit at the Clifton Park bandshell filled my timeline. They were all so stylish and cool. And they talked about loneliness and isolation in a way that resonated during a particularly lonely time. “Can’t be the only one,” frontman Brendan Yates crooned on “Alien Love Call,” and I listened wholeheartedly, wondering if anyone ever felt the way I did and feeling reassured that even Yates felt like an alien sometimes.

Turnstile say they’re a Baltimore band, but really, their roots are in Burtonsville, a suburb between Baltimore and D.C. Yates has said in interviews that Burtonsville is 10 to 20 minutes from each city, which is true only if you’re talking about the absolute city borders and you are the only person on the road. He grew up taping songs off DC101, the same alternative rock station to which I grew up listening. He was obsessed with “Breathe” by The Prodigy and called to request it so many times that the DJ knew him by name.

Yates and Turnstile’s lead guitarist Brady Ebert started playing music together when they were very young, forming a band to play at a community event called “Burtonsville Day.” Yates once said in an interview that Beach House’s “Take Care” reminded him of his first love. Maryland was in his blood. In my early days of infatuation, I listened to a ton of interviews with Yates; he spoke deliberately but with a quiet confidence, letting the words roll around in his mouth, and I always nodded along, feeling an instant connection with my fellow Marylander.

I wish I’d been cool enough to see Turnstile in a basement or community center. Their 2016 album “Nonstop Feeling” was an instant classic; 2018’s “Time & Space” pushed the boundaries of hardcore. By the time I got into them, they’d taped a Tiny Desk concert, pushed the boundaries so far that people were calling them butt rock, and sold out the 9:30 Club. I bought a ticket from a dad on Facebook, stood on the balcony, and watched the crowd mosh to their entrance song, Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance with Somebody.” The night felt euphoric.

The next time I saw Turnstile, with fellow Baltimoreans JPEGMafia and Snail Mail, they sold out the Anthem, a cavernous venue that can hold up to 6,000 people, and unleashed confetti during “T.L.C.” Soon, my dad heard them on DC101. They had a song in a Taco Bell commercial. They were nominated for a Grammy. They threw out the first pitch at an Orioles game. (Guitarist Pat McCrory and his family are huge fans.) I was so proud of them. Those were my guys.

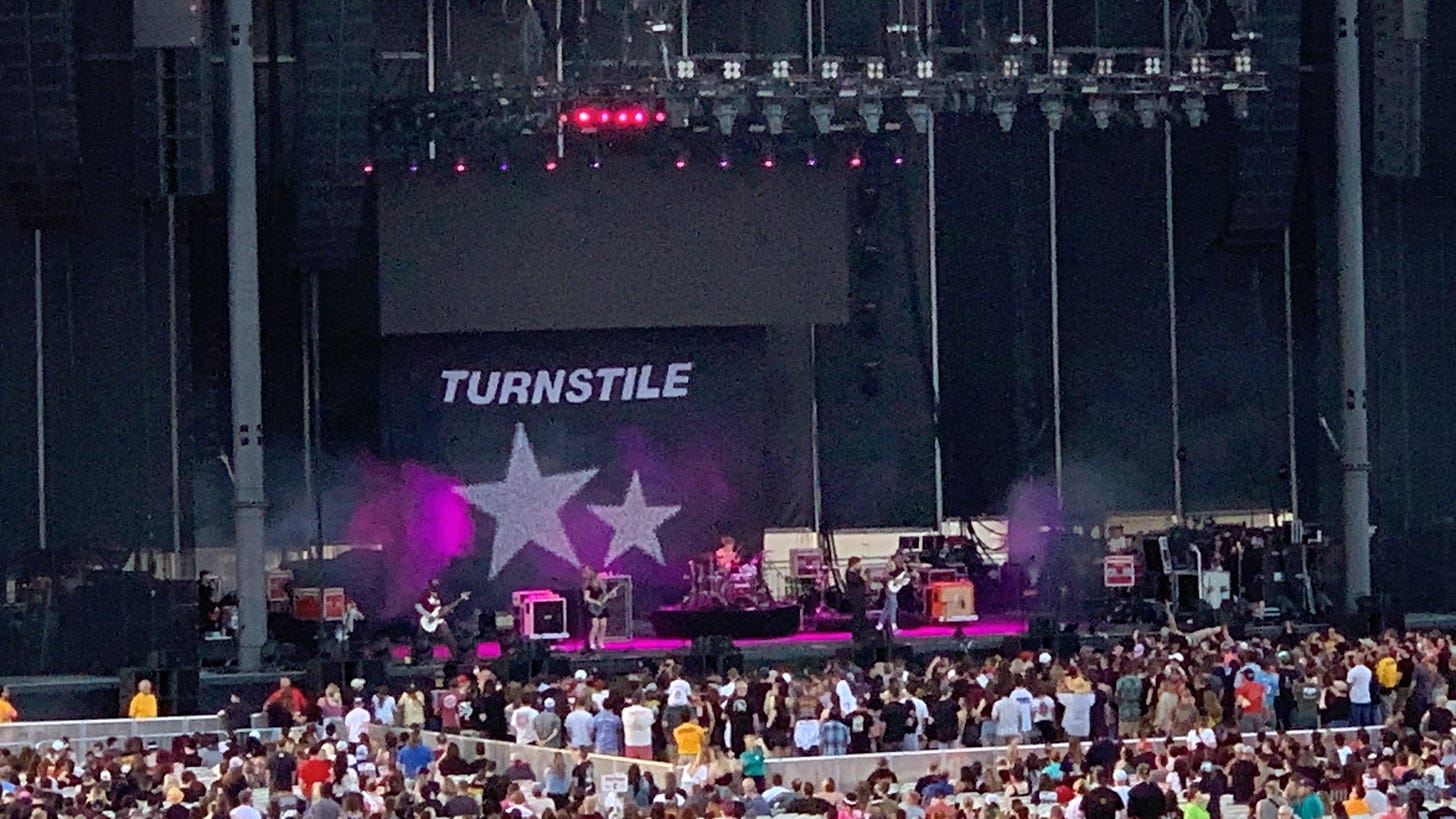

In 2023, Turnstile embarked on a mammoth tour opening to blink-182, which I saw at Hersheypark almost exactly a year after the 9:30 Club show. It was weird. Since I’d become a Turnstile fan, I’d started going to shows almost weekly, mostly to see local bands in small venues. I hadn’t been to an arena show in years; I felt overwhelmed by the crowds and missed the intimacy of even the most corporate of sweaty clubs. Most people at this show were 38 years old and wore blink-182 shirts. A small mosh pit opened up near the back of the field during Turnstile’s set. I felt like the crowd did not appreciate them enough. The gatekept had become the gatekeeper; the punished the punisher.

Most of the weirdness subsided when blink-182 came out and I started screaming along to songs that felt like they lived in my bones. But my weird feelings about Turnstile lingered. How much longer could they do this? I wondered to myself. Is this the end of the line?

During their ascent, Turnstile parted ways with Ebert. On their spring 2022 tour, Greg Cerwonka from Take Offense had filled in as lead guitarist. A couple guys behind me had chanted, “Where is Brady?” when Cerwonka played one of Ebert’s solos; his guitar tone just wasn’t the same. In August, the band made an official announcement on Instagram that Ebert was no longer with the band; the following year, they added British guitarist Meg Mills on rhythm and moved rhythm guitarist McCrory to lead.

I wondered if the band would rip as hard without Brady’s signature riffs. I worried about them leaning too hard into the Blood Orange vibes they’d tapped into on “Glow On.” In 2024, when the band showed up at the Grammys in disappointing outfits, I felt like the end was nigh. They’d probably put out one more album and call it quits shortly after, dispersing across the country to settle down, work in fashion, focus on their other bands. I put “Turnstile breakup” on my 2024 bingo card, and, when it didn’t happen, on my 2025 bingo card.

When Turnstile announced “Never Enough,” I wasn’t excited. The lead single and title track sounded like the more atmospheric twin sister of “Mystery” from “Glow On.” They’d worked with Will Yip, who has worked with many of my favorite bands but whose production style I do not enjoy—all glassy vocals, heavy treble, and wet drums. Charli XCX declared that it was “Turnstile Summer.” And maybe I was just upset that I missed their huge benefit show at the Wyman Park Dell, but I felt like the singles and the band’s narrative around them were all style, no substance.

Still wanting to be part of the zeitgeist and open to giving “Never Enough” a second chance, I bought tickets to the band’s “visual album” at a local Regal, right before they sold out. It was clear who was there to see Turnstile that night—they were all wearing bucket hats and camo and Turnstile shirts. Someone behind me in line for concessions joked, “This one’s called Never Enough. What’s the next one going to be—‘Turnstile: Way Too Much’?”

The film’s visual style is similar to their “Turnstile Love Connection” film from 2021, but they trade the soft pinks and baby blues for a more muted color palette, inspired by a row of Baltimore homes that make an appearance in the film. The color grading is all A24 grainy. The title track shows each band member playing alone in a different part of the world. Next, they’re playing “Sole” to a crowd of moshers in a park, playing the peppy “I Care” in the studio.

It’s these studio scenes that captivate me the most, full of simmering tension in a small space. In “Sunshower,” everyone’s having a good time, and Yates is sitting down, singing, “And this is where I wanna be/But I can’t feel a fuckin’ thing,” looking sad as hell. Another highlight is “Light Design,” which features the band members dancing in an empty theatre, their silhouettes stretched across the stage as Yates sings, “I hold my head and cry.” It’s lonely at the top!

And it’s especially lonely without his brother. The band has shared little about the context for Ebert’s departure, and I won’t speculate on it, but it looms like a spectre over “Never Enough.” The lyrics of “Time is Happening” are few, but they speak volumes:

Time is happening

Ever-passing me

Circle back again

Lost my only friend

Time to let you know

Arms will let you go

So I nod and wave

Kissed and pulled away

Time is happening

Devastatingly

Circle back again

Lost my only friend

The visual for this song features a young boy dancing in a fountain, and it makes me nostalgic and sad. I imagine the two boys who played Burtonsville Day together, now apart.

There’s an undercurrent of melancholy throughout “Never Enough.” The lightness and hope that characterized “Glow On” are replaced by a sense of weariness, underscored by frequent shots of a metronome that stress the passage of time.

Sonically, the album builds on the previous album’s grooves but sands off the edges, cloaking Yates’ plaintive voice (and everything else) in layers of reverb. Features from Hayley Williams, who called the band “[her] Fugazi,” Faye Webster, and A.G. Cook are totally inaudible. Moments of momentum burst into indulgent interludes—droning synths, static, a flute solo (during which a jacked Mary Jane Dunphe breaks into interpretive dance during the film), downtempo solo numbers with just Yates and his synths.

The band’s newfound sheen frustrates me at times, but the songs are still earworms, and the disappointing singles reach me in new ways in the film. “Look Out for Me” starts out like “Fly Again” part 2 before bubbling into a Baltimore club–influenced outro. It’s not unlike “Mind’s a Lie” from last year’s excellent High Vis album “Guided Tour,” which blends baggy club beats with anthemic post-hardcore.

In his otherwise stellar review, Enis dismisses this outro as “generic house beats” and argues that Turnstile spends too much of the album nodding to their influences outside hardcore. Yes, the interludes can feel bloated and incongruous to some. But to me, this particular outro is an ode to the hometown they love that takes on a new poignancy in the film. After a frenetic drive in a Volvo, past a bench that reads, “Baltimore: The Greatest City in America,” the video cuts to Yates sitting alone in the car in the middle of Wyman Park, looking absolutely despondent. The song samples “The Wire”—“You gonna look out for me?” A throng of people in black descends upon Yates. A hand on his shoulder. Cut to birds flying over the ocean, another of the film’s motifs.

The end of the video shows the view from the rear window as the car drives through Baltimore. It reminds me of nights I’ve driven around the city after shows, meandering after taking a wrong turn or falling victim to a one-way street—journeys that began as mistakes but now are comforting memories. It might be lonely at the top, but I hope Turnstile always finds comfort in their home.